What follows is a discussion on the design of a weapon that is somewhat unique in the annals of ancient Graeco-Roman artillery. Its very name “Polybolos” (lit. “many thrower”) implies this weapon was the torsion-powered, semi-automatic repeating catapult or bolt-shooter described in detail by Philon of Byzantium in his work “Belopoietica” (Marsden, 1971, 147-155). Possibly dating to 300 BC and constructed by Dionysius of Alexandria in Rhodes, this innovative machine uses a windlass operated double chain drive running over pentagonal sprockets to move a slider back and forth. It also incorporates a cam mechanism to translate linear movement into rotary motion to turn a long roller that feeds bolts, one at a time, from a magazine into the groove on the slider. Both innovations are remarkable for their first known appearances in European technology. Trip mechanisms are also used to cause the trigger to capture and then release the bowstring (Wilkins, 2024, 1). To appreciate the complexity and elegance of the design, armed with Philon’s description a working Polybolos was reconstructed by Alan Wilkins, FSA. The video clip below shows the machine in action:

Automatic action With the forward rotation of handspikes on a windlass, which is connected to the rear sprockets, the slider moves automatically forwards, whereupon a pin attached to the slider engages and follows the helical cam groove of the roller above. The roller rotates clockwise until the lengthwise slot is aligned with the corresponding opening of the bolt case, or magazine, at which point gravity feeds a bolt into the longitudinal groove. As the slider reaches the extent of its forward motion, the bowstring is fed beneath the claw-like fingers of the trigger. Another pin engages the trigger release lever locking the claw over the bowstring.

Rotating the windlass in the opposite direction reverses the direction of the chain drive to pull the slider rearward and, in so doing, rotates the roller anticlockwise. When the longitudinal slot is aligned with the groove in the slider an arrow is gravity fed onto the latter. The slider continues rearward until a fixed pin engages the protruding lever of the trigger mechanism freeing the claw to pivot upward and release the bowstring. At this point the twisted skeins of sinew-rope propel the two bow arms forward dragging the bowstring along the slider to discharge the bolt. The continuous backward and forward rotation of the windlass in this way enables an operator to launch a succession of bolts relatively swiftly.

The chain drive mechanism produces an impressive rate of fire when compared with a reproduction of a standard three-span Vitruvian catapult (Latin: sing.

catapulta; pl.

catapultae). Testing by members of the

Roman Military Research Society (RMRS) revealed that Wilkins’ Polybolos could shoot six bolts in the time taken to discharge two using the Vitruvian machine and a two-man crew. With this impressive rate of fire there must have been a very sound reason for the Polybolos not continuing in service after the third century BC. Why, then, was the Polybolos unsuccessful?

Design ahead of its time? The main problem seems to be that it did not offer a huge technological leap forward in terms of firepower. While one man can singlehandedly operate the Polybolos, the semi-automated loading and firing process results in the string being drawn at essentially the same rate as other non-automated machines. Allowing gravity to feed the bolts is therefore not much faster than allowing a loader to place them on the slider against the bowstring. Moreover, the non-automatic system allows the ballistarii (“artillerymen”) more time to aim between shots. Philon makes the claim that the Polybolos was too accurate (“...the missiles will not have a spread...”), but one might question whether Philon ever saw the machine in action, because there is no way that successive bolts would stay in a tight group except at close ranges [1]. Indeed, well before the maximum range quoted by Philon - “...little more than a stade” (approximately 200 m) - the bolts would have dispersed, as they can be seen to do when shooting modern reconstructions of standard, non-automated, bolt-shooters [2]. The Polybolos is clearly a much more complicated machine, with many more constituent parts, than the standard bolt-shooter. It would have been more costly to construct and maintain. For example, the Wilkins’ reconstruction used about 150 pins to join the links of the two chain drives, and that may be the Achilles heel that led to its not having “found a noteworthy use” by Greek, or indeed Roman armies. Every pin would have to withstand the strain of drawback, and if even one pin snapped - literally “the weakest link” - then the machine would be out of action. Yet it is intriguing to know whether a full power Polybolos would be a viable weapon. Having seen Alan Wilkins’ reconstructed Polybolos in action several times over the years, and having been lucky enough to shoot it, the machine uses a complex yet elegant mechanism, the operation of which is simple to master. Yet the design is not without its problems.

Underpowered Firstly, most, if not all, reconstructions of the Polybolos appear severely underpowered. This is not a criticism of the reconstructions themselves, or of their builders, however. Most of these machines are simply proofs of concept - full size working models if you prefer - aimed at “bringing to life” Dionysius’ invention. Their constructors did not necessarily set out to reproduce a fully tensioned catapult. Rather, most builders are simply intrigued by the repeating concept and determined to investigate how all the complex parts might have fitted and worked together. Leaving the machine underpowered, therefore, makes some sense as the complete mechanism is somewhat of an unknown quantity. The precise materials used in its construction are not known, although we can infer much from the parts of ancient catapults that do survive. Nor do we know how robust these different parts were or need to be. We have no idea whether the whole mechanism could have coped with the stresses on the individual components or whether it could have operated efficiently with the amount of potential energy stored in fully tensioned sinew-rope springs. There is the inherent danger of the machine literally destroying itself under tension. Until a foolhardy individual builds a full power catapult fitted with the automated loading/release system, this will remain a “known unknown”.

All of the above, however, has been a preamble to a long running thought experiment. Taking Wilkins’ Polybolos as the benchmark, it is obvious from shooting his reconstruction that the bolts do not fly very far: about six metres rather than the hundreds for a truly effective war machine. This is hardly surprising since the spring frame is deliberately underpowered for reasons of safety when being demonstrated in public. The performance is not helped as the Wilkins example, and all similar reconstructions, uses flightless bolts. Once again this is not that surprising. The automated feed system, with its magazine and grooved roller, would appear to rule out the use of fletching, but the absence of feathers, fins or vanes (otherwise known as fletches or flights) will adversely affect the aerodynamic stabilisation of bolts or darts. Thus, we are left to question what would happen if flightless bolts were used in a fully tensioned Polybolos? How would they perform? Would they be stable in flight? Would the bolts fly true? How accurate would the catapult prove to be, and what ranges could be achieved? Answering these questions would certainly demonstrate the viability, or not, of a fully tensioned Polybolos as a weapon.

Just as the bolts shot from the famous 3rd-century AD Chinese repeating crossbow had no flights at all, nor do those used in Wilkins’ reconstruction. This, however, contradicts Philon as he informs us that the Polybolos shot an unnotched, one cubit one dactyl long (481.7 mm) [3] missile with three feathered flights. However, as the missiles were delivered from the magazine to the slider via a grooved roller, “the flights could be as long as you like, but could not protrude much from the surface of the arrow, otherwise they would interfere with the automatic loading” (Marsden, 1971, 178: Note 109).

Arrow anatomy Before proceeding it might be beneficial to describe the anatomy of an arrow or bolt. Broadly speaking any arrow (or bolt) is designed to deliver an arrowhead (also known as a “point”) to the intended target. There are numerous variations in points to deal with different targets and circumstances. Broadheads and barbed heads are typically used for hunting and/or against unarmoured targets, while bodkin points were developed to penetrate armour. The selection of arrowheads

pictured gives an idea of the variety available at different times and for different uses. Regardless of the styling, arrowheads are fixed to one end of a shaft, traditionally wooden although modern arrow shafts are more likely to be of aluminium or carbon fibre. At the opposite end of the shaft is fletching consisting of feathers, fins, flights or vanes, each of which individually is known as a fletch, and collectively used to stabilise the arrow in flight and improve its accuracy. Traditional fletching consists of three matched half-feathers that are equally spaced at 120° intervals around the shaft’s circumference. In English archery, the male or “cock” feather is used on the outside of the arrow, while the other two stabilizing feathers are referred to in some quarters as “hens”. Wing feathers have a natural curvature that helps spin the arrow in flight and thus stabilise it. Traditional archery lore has it that a right-handed archer should shoot a right-winged feather and right-handed helical, and a left-handed archer should use the opposite.

So, the arrows shot from a traditional bow typically have three fletches arranged as pictured. Some horse-archers prefer four fletches as this makes it easier to orientate and nock each arrow on the bowstring while in the saddle of a moving horse. Fletches were traditionally attached with glue and silk thread. Feather fletches impart a natural spin on an arrow due to the rough and smooth sides of a feather and their natural curvature in accordance with which wing the feather came from. Vanes, such as modern plastic ones, need to be placed at a slight angle (called an offset fletch), or set into a twist (called a helical fletch) to create the same effect, but all are there to impart stability to the projectile to ensure it does not tumble during flight.

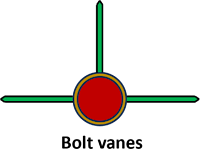

The design of ancient catapults, however, presents a problem for fletching bolts. Before shooting, each bolt is set in a semi-circular grove in the catapult’s slider (see

below) and butted up to its bowstring (a nock is not required). The groove’s profile does not allow the bolt’s vanes to be set at 120° intervals around the shaft’s circumference. Rather,

Tastes Of History’s reproduction bolts have two lateral vanes fixed horizontally, and one vertical dorsal vane (the equivalent of the cock feather), as

shown.

A large dorsal vane, however, would hinder the efficient stacking of bolts in the type of vertical magazine described by Philon. It is quite usual for crossbow bolts (quarrels), such as the Mediæval examples

pictured, to have only two horizontal vanes. This would be a simple compromise yet, as previously mentioned, Philon stated: the three “flights could be as long as you like but could not protrude much from the surface of the arrow, otherwise they would interfere with the automatic loading”.

Figures 1 to 3 below are our attempt to illustrate how bolts are fed, one at a time, from the Polybolos’ magazine into a groove cut into its long roller which, in turn, rotates to drop each bolt into the groove on the slider. Note that in the Wilkins’ reconstruction, and as evidenced in the video

above, two brass guides prevent the bolts from prematurely dropping out of the roller groove. These guides have been omitted in the following diagrams for clarity.

In Figure 1, the roller rotates clockwise on an axle until the next bolt drops from the magazine into the roller groove. As the mechanism reverses direction so the roller rotates anticlockwise (Figure 2) until the bolt drops into the slider groove. The problem with this configuration, as shown in Figure 3, is that a bolt with a dorsal vane will foul on the slider groove and prevent the bolt seating correctly. Ideally, the bolt should be presented the other way up, but this would mean loading the magazine with the dorsal vanes downward and they would then not seat correctly in the roller groove. So, despite Philon’s attestation that each bolt had three feathers it seems more logical that only two vanes should be used as is the case for crossbow quarrels. Moreover, removing the dorsal vane allows more bolts to stacked in the magazine, and the two-vane solution mitigates the feed issue while retaining the stabilising effect of fletching (Figure 4).

Two alternative solutions may also address the automatic feeding issue and the current lack of fletching. The first echoes Philon but proposes adding a fourth fletch (three of which are shown

below in black) for symmetry. The shaft at the point where the fletches are adhered would need to be of sufficient diameter so the bowstring connects with the bolt shaft and not the fletches/vanes. The latter circumstance would undoubtedly lead to a potentially dangerous misfire.

The mock-up shown above is based on a bolt recovered during the 1922-1937 excavations in the Roman garrison town and Sassanid siege-works at Dura-Europos in Syria (see below). In this design, the vanes fill where material was removed from tail of the Dura-Europos example such that they do not protrude excessively from the shaft as Philon suggests. Of note, a tapered wooden shaft may not be the most appropriate for the feed system, but the thicker rear section ought to act as a useful counterweight to balance the iron bodkin. Experiments with both tapered and parallel shafts would be necessary to determine the most efficient bolt design.

.jpeg)

The inspiration for a second possible solution came from a somewhat unlikely source, namely the “Hale Rocket”. In 1844 William Hale (1797-1870) patented a new form of rotary rocket design that improved on the earlier

William Congreve design. Removing the stabilising guide-stick from Congreve’s rocket, in its place Hale vectored part of his rocket's thrust through canted exhaust holes. This imparted rotation to the rocket about its longitudinal axis thereby improving its stability in flight [4]. The three curved fins reminiscent of an arrow's fletches were, most notably, in-line with the rocket’s cylindrical body. Could a similar configuration be used for the shaft of a Polybolos bolt? Could the fletches or vanes be fixed to a reduced diameter shaft so as not to foul the feed system, and would this actually work?

The first pattern, shown below, uses a standard 460 mm long, untapered bolt typically shot by one-cubit, or two-span, catapult reproductions. Note that three offset vanes have been carved into the rear portion of the shaft along its longitudinal axis. A sufficient mass of material is retained to mitigate the possibility of the shaft shattering as the propelling force is transmitted from the bowstring to the bolt.

The next step will be to produce a number of example bolts and shoot them. Future tests will aim to prove the concept and determine which of the two bolt designs will: (1) feed cleanly from the Polybolos' magazine, (2) engage with the mechanism, (3) shoot safely, and (4) improve in-flight stability. Until then, bon appétit!

References:

Marsden, E.W. (1971), “Greek and Roman Artillery: Technical Treatises”, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilkins, A. (2024), “Roman Imperial Artillery”, Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 1-3.

Endnotes:

1. There is little or no evidence beyond Philon’s description to prove the Polybolos was anything more than an idea. Most likely it was an unrealised one.

2. As with many automatic weapons systems, the Polybolos does tend to launch multiple bolts consistently at the same point in space. While this does produce a rather desirous 'mean point of impact', it is less than ideal if the intention is to engage and hit multiple targets in rapid succession.

3. The modern equivalents to the ancient Greek units of measurement are:

1 dactyl 19.3 mm (0.76 in)

1 palm (4 dactyls) 77.1 mm (3.04 in)

1 span (12 dactyls) 231.2 mm (9.12 in)

1 foot (16 dactyls) 308.3 mm (12.16 in)

1 cubit (24 dactyls) 462.4 mm (18.21 in).

4. Winter, F.H. (1990), “The First Golden Age of Rocketry: Congreve and Hale Rockets of the Nineteenth Century”, Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, p. 321.

.jpeg)

.png)