This ‘How to:’ guide is a follow up on a previous post aimed at readers wishing to recreate simple yet effective historical costume. The focus for this guide, however, is on the ancient Greeks and the typical clothing worn from the 5th century BC Classical period until the 1st century AD and Roman rule. Three garments were the basis of Classical Greek dress: the khiton (pronounced kite-n), the peplos, an overgarment worn by women, and the chlamys (pronounced klom-iss), a cloak. These three garments were draped and belted to create various styles. To this list has been added the himation, a form of dress similar to the more famous Roman toga.

First off are a few practical pointers for the modern maker:

Material The only truly acceptable cloth should be made from the natural fibres of linen or wool. It is recognised that sometimes modern cloth contains a mixture of these and cotton. This is tolerable compromise for those seeking to be as accurate as possible since the mix of fibres will not adversely affect the appearance or the draping qualities of the base material.

Construction There is no reason why seams that are not immediately visible cannot be machine stitched. There are some people for whom this is an anathema as it is ‘not historically accurate’. We would argue that careful use of machine stitching is merely a practical measure (we live in the 21st century and are not actually ancient Greeks) providing visible seams, such as those in collars, sleeves and hems, are hand sewn.

Fastenings Garments that were not sewn together were typically fastened using long pins (fibulae), brooches, or buttons and toggles made of bone or wood.

Himation

The himation (ancient Greek: ἱμάτιον / hə-MAT-ee-un) is the ancient Greek equivalent to the Roman toga. In its simplest form it was a large rectangular piece of woollen cloth, approximately 4 m to 5 m in length and 1.2 m to 1.5 m wide, worn by ancient Greek men and women from the Archaic through the Hellenistic periods (c. 750 BC to 30 BC). It was typically worn over a man’s khiton or woman’s ‘peplos’ (see below) being draped about the wearer’s body from shoulder to ankle. As shown right, men sometimes wore the himation alone without a khiton underneath. In this manner it served both as a khiton and as a cloak and was called an ‘akhiton’. Many vase paintings depict women wearing a himation as a veil covering their faces.Draping It is unlikely that the himation can be simply 'slipped' on. Rather it may take the assistance of one or two people. Yet, evidence on how to put on a himation does not survive and modern wearers may have to experiment with the most effective way of doing so. The following guidance is offered to those assistants charged with dressing the himation wearer:

1. The wearer stands erect with their arms extended laterally at shoulder height, i.e. in a cruciform stance. Other than holding a fold or slowly rotating when instructed, there is little else for the wearer to do.

2. The cloth is prepared for donning by gathering the folds, which are then placed, from behind the wearer, over their left shoulder. The folds should be uppermost and hang down the wearer’s front, with the bottom edge reaching to between calf and ankle. The folds should be adjusted as required to drape properly. The wearer can assist by bending his left arm at the elbow and gripping the material in place.

3. Keeping the folds together, drape the material across the wearer’s back, looping up under their right arm, across the chest (the wearer’s left hand must be out of the way) and once again over the left shoulder. Depending on the available space it may be advantageous to get the wearer to perform a slow quarter or half turn to the right.

4. The remaining material should be draped along the length of the left arm to hang towards the left foot.

Khiton

The khiton (χιτών) is the base garment worn by both men and women. Essentially it is a rectangular piece of cloth folded laterally to form a tube with one side left open. The back corners were pinned to the front to form shoulder straps. Alternatively, khiton could be sewn at the shoulders and sewn from the underarm to the hem to form the tube. The difference between the sexes is the overall length of the garment and where the hemline ends. For women, dresses are typically shown full length with the hemline at least to the ankle. By contrast, Greek men tended to wear their khiton quite short above the knee at mid-thigh level allowing more freedom of movement in exercise, manual labour and in warfare. Some depictions show very short khiton barely covering the genitals [1].

Exomis

A variation on the khiton was the exomis worn, it seems, by men only (although some goddesses might be depicted in one). As for a khiton, it is a rectangular piece of cloth approximately 2 m long and at least 1 m wide worn with the hemline at mid-thigh or shorter. The material is folded in half laterally about the wearer’s body with the top of the fold beneath right armpit and fastened at the left shoulder. The exomis is then belted and the material arranged to drape evenly.Material For most people, clothing was made predominantly of wool or linen. The wealthy could afford very finely woven cloth, with some examples being especially sheer or translucent. For our purposes, the basic garment is easily reproduced from a rectangular piece of cloth approximately 2 m long and between 2 m and 3 m wide.

Pattern As in our previous post, we will focus on a pattern for a woman’s khiton as the men’s version is essentially a shortened form either with or without short sleeves. In its simplest form the Doric style khiton is a folded rectangle of cloth with the two halves fastened with multiple fibulae (pins) or buttons at the shoulders, or simply sewn together. Doric style dresses worn by ancient Greek women may well have been left open along the line B-C (refer to the diagram below), with the two halves of the dress belted in place. If you are feeling particularly risqué then you could follow the ancient example, but we would suggest, for modesty’s sake alone, that the seam along B-C is sewn.

An alternative is the Ionic style khiton which was also a large piece of fabric folded laterally and then pinned at intervals along the arms and at the shoulders. Belted it formed voluminous sleeves when carefully draped.

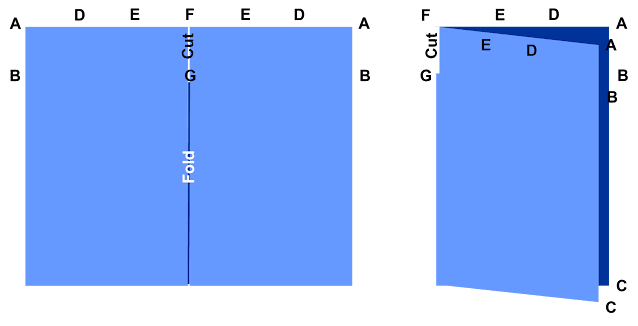

In the diagram above, the head hole is formed between D-E which, from experience, needs to be at least 25 cm to 30 cm (c. 10 to 12 inches) wide. When folded in half, and if you decide to sew the shoulders together between A-D and E-F, then the cloth must be cut at F-G to allow the right arm to pass through. If you prefer to simply pin the garment at the shoulders with brooches at D-D and E-E, then the cloth would fall on each side and cutting the F-G armhole would not be necessary [2].

In the pattern above the rectangle of cloth needs to be approximately 2 m long and at least 3 m wide (once folded it will be 1.5 m wide).

Belts Khiton should be belted at the waist. Excess material can be pulled up and bloused over the belt to achieve the desired length. Sometimes women’s dresses were belted twice, once at the waist and again at the hips, giving a double-bloused effect. Similarly, they are also depicted belted high under the breasts, or cross-belted over the chest and tied at the waist.

Peplos

While the Doric style khiton is perfectly acceptable attire for women, a peplos (Greek: ὁ πέπλος) is the more typical clothing for women in ancient Greece by about 500 BC during the late Archaic and Classical period. As with the khiton, the Doric peplos was a body-length (A-C) garment made from a rectangle of cloth folded about the wearer and open on one side of the body. In this case, however, the top edge was folded down about halfway to, or below, the waistline thereby forming an overfold called an apoptygma (pictured below). The folded top edge was pinned from back to front at the shoulders (D-D, E-E) and the garment gathered about the waist with a belt. The shorter, waist-length apoptygma might be belted beneath the material, while longer, below the waistline apoptygma are shown belted just below the bust. In either style the apoptygma provided the appearance of a second piece of clothing. The overfold should be arranged to drape evenly.

Hats and Cloaks

Ignoring helmets, ancient Greek men are often depicted wearing broad-brimmed, bell-crowned hats to protect against sun and rain. Called petasos (below left) they seem popular with travellers and may have been made of straw, felt or leather. A simpler style of straw cap or tatulus (below middle), perhaps favoured by labourers, were also worn. There are far fewer depictions of women wearing hats but this does not they were not worn. In the artist’s impression below right, the lady is shown with her outer garment, a himation, draped over her head, which is probably how most women went abroad outdoors. In ancient societies, particularly the Greeks and Romans, for a woman to be out in public without her head covered or with long flowing, loose hair was seen as a sign of impropriety - loose hair, loose woman. With her head dutifully covered she sports a small straw sun hat known as a tholia.

As instead of the himation or akhiton previously mentioned, when outdoors or travelling ancient Greek men wore a chlamys (right), a short hunting cloak. Once again it is basically a rectangle of, usually, woollen cloth that was draped over the left shoulder and pinned on the right. It could be worn over a khiton or alone, the latter being considered ‘manly’ to endure the elements in a single garment.If one was to take inspiration from the earlier Etruscans, then a square-cut or semi-circular form of poncho known as a tabenna was seemingly popular in the 7th to 5th centuries BC.

Footwear

Going barefoot was common, especially for children, but the ancient Greeks also wore simple leather shoes when outdoors. Carbatina for example, featured soles and uppers cut from one-piece of leather. Loops cut around the leather’s edges allowed laces to pass through and draw the uppers together about the foot.

Unsurprisingly there is a large variety of footwear depicted in ancient Greek art and sculpture ranging in styles from soleae, sandals held in place by a leather thong or tongue between the toes, to krepidea that enclosed more of the foot. Ankle and calf-height boots are also shown [3].

Endnotes:

1. We are all for ‘authenticity’ but in a school or at a public event this might not be a wise choice professionally and legally speaking.

2. In other words the arms pass through the gaps A-D and E-F.

3. If portraying an ancient Greek character avoid wearing Roman caligae. While these are widely available to buy online, they are the distinctive and instantly recognisable footwear of Roman soldiers and thus wholly inappropriate for the Classical Greek period.

No comments:

Post a Comment