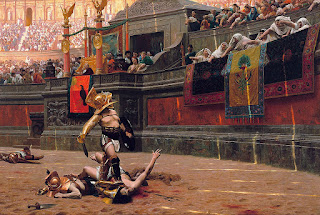

The popularity of gladiatorial games led to ever more lavish and costly ones featuring armed combatants entertaining audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Irrespective of their origin, gladiators offered spectators an example of Rome's martial ethics and, in fighting or dying well, they could inspire admiration and popular acclaim.

All were slaves If you have watched Ridley Scott’s 2000 film “Gladiator”, or the more recent “Gladiator II” (2024), you can be forgiven for thinking that all fighters in the arena were slaves. In one sense, this is true. The vast majority fighting in the arena were there under duress, drawn mainly from the ranks of criminals or prisoners-of-war. A few might achieve “celebrity status” [2] - if contemporary high and low art (such as graffiti) is anything to be believed - but in the strict social hierarchy of the Roman world, all gladiators were counted among the

infames [3]. In Roman law, anyone condemned to the arena or the gladiator schools (

damnati ad ludum) was a

servus poenae (slave of the penalty), and considered under a sentence of death unless manumitted (freed).

Only slaves found guilty of specific offences could be sentenced to the arena while citizens found guilty of certain offences could be stripped of citizenship, formally enslaved, then sentenced. Slaves, once freed, could be legally reverted to slavery in certain circumstances. Arena punishment could be given for banditry, theft, arson, and for treasons such as rebellion, census evasion to avoid paying due taxes, and refusal to swear lawful oaths.

Offenders seen as particularly obnoxious to the state (noxii) received the most humiliating punishments. By the 1st-century BC, noxii were being condemned to the beasts (damnati ad bestias) in the arena with little chance of survival, or were simply forced to kill each other. By the early Imperial era, some were compelled to participate in humiliating and novel forms of mythological or historical enactment, culminating in their execution. Those judged less harshly might be condemned ad ludum venatorium (combat with animals) or ad gladiatorium (combat with gladiators) and armed as thought appropriate. These damnati at least might put on a good show and retrieve some respect and, very rarely, survive to fight another day. Some may even have become “proper” gladiators. Yet, as infames, gladiators were largely despised as slaves, socially marginalised, and segregated even in death.

‘He vows to endure to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword’ (Petronius. Satyricon, 117)

We know from contemporary accounts that some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing as freemen by appearing in the arena. Their reasons for giving up their freedom and risking serious injury or death in the arena may have been many and varied. A condemned bankrupt or debtor, for example, might be accepted as novice (novicius) whereupon he could negotiate with his lanista (manager of gladiators) or editor (sponsor of the games) for the partial or complete payment of his debt. For some, the potential rewards and the opportunity to escape poverty were motivation enough. For others, perhaps it was the fame and celebrity status that appealed. A few may have entered the arena purely for the thrill or love of fighting.

In the Imperial era, these volunteers required a magistrate's permission to join a ludus (gladiator school) as auctorati. If granted, the school's physician assessed their suitability. Their contract (auctoramentum) stipulated how often they were to perform, their fighting style and earnings. Faced with runaway re-enlistment fees for skilled auctorati, the emperor Marcus Aurelius set an upper limit at 12,000 sesterces. Among the most admired auctorati were those who, having been granted manumission, volunteered to continue fighting in the arena. Some of these may have been highly trained and experienced specialists for whom there was no other practical choice open to them. The legal status of auctorati - whether slave or free - remains uncertain.

Bound by sacred oath All prospective gladiators, whether volunteer or condemned, were bound to service by a sacred oath (

sacramentum) vowing “to endure to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten, and to be killed by the sword” (Petronius, Satyricon, 117). Novices trained under teachers (

doctores) who were most likely retired gladiators skilled in particular fighting styles. Lethal weapons were prohibited in the schools - weighted, blunt wooden versions were probably used. Fighting techniques were probably learned through constant rehearsal as choreographed “numbers” to produce the preferred elegant, economical style. Training included preparation for a stoical, unflinching death.

Gladiators were typically accommodated in cells, arranged in barrack-like buildings set around a central practice arena. Once in the school their training required intense commitment, and discipline could be extreme, even lethal. Those who performed well, however, could ascend through a hierarchy of grades (sing. palus) in which primus palus was the highest [4]. Indeed, Juvenal describes the segregation of gladiators according to type and status reinforcing the idea that within the schools were rigid hierarchies: “even the lowest scum of the arena observe this rule; even in prison they are separate.” As most combatants were from the same school, segregation kept potential opponents separate and safe from each other until they enter the arena.

There were many different types of gladiator. One of the most recognizable was the retarius, a term derived from rete meaning “net”, who wore no helmet and darted about the arena equipped with a net, a trident and a dagger. The murmillo, armed with a sword and small shield, was named after the Greek saltwater fish mormylos because of the long, high crest on his helmet. A retarius fighting a murmillo was a popular pairing symbolising the “net man”, or “fisherman”, hunting the “fish”. The retarius could also be pitted against the secutor (“pursuer”) armed with a sword and large shield. The latter wore a plain helmet with no crest, protecting him from being snagged by the retarius’ net, which also had two smaller eyeholes as defence against his opponent’s trident. Gladiator specialisation was based on physical attributes. The most heavily armed had to be strong, while the likes of retarii needed to be quick, sure-footed and agile. Ethnicity may also have been a factor since part of the entertainment was role-playing. Gladiator bouts were as much about theatrics as violence: in modern terms, mostly MMA with a dash of WWE [5].

To the Death Gladiator deaths in the arena were probably not as high as many modern commentators often portray. Gladiators were expensive to provide for and train, and perhaps to protect the investment, most only fought two or three times per year.

A gladiator’s price was fixed according to his rank, status and degree of success, with their market value being highly relevant if they died in the arena. His death became a chargeable item by which the owner, usually the lanista, would be recompensed. In the 1st-century AD a common day-labourer in Rome typically could expect to be paid two sesterces per day. Compare that with a first grade gladiator in the lowest class of

munera who may have commanded a maximum price of 5,000 sestertii which, according to Susanna Shadrake, is the equivalent of about £32,000 today. This is hardly a trivial sum of money or investment to be carelessly discarded (Shadrake, 2005, 91).

The Emperor Augustus for example, prohibited combats sine missio (in this sense “without mercy”), or to the death. This was partly to recognise the investment value of a skilled fighter but mostly to limit extravagant displays and the political value to those staging contests (editores) by influencing voters with lavish entertainment. In the 1st-century AD, the chances of survival have been estimated at 9:1 based on analysing the results of contests. If a gladiator lost, the ratio reduced to 4:1 and ultimately depended on a successful appeal for missio (“mercy”). Under later emperors, however, a gladiator’s chances of survival deteriorated as more and more fights were to the death.

If a gladiator survived three years of fighting in the arena, however, he would win his freedom. Those who did often became teachers in the gladiator school; and one of the skeletons excavated at Ephesus in Türkiye appears to be that of a retired fighter (Kupper & Jones, 2007). None of this denies the facts that gladiators died in the arena, just that their chances of survival varied at different times.

Men only For convenience we have used the male pronoun throughout, but this usefully reveals another “Hollywood” myth: that gladiators were all men. To be fair to the film “Gladiator” there is a scene where the hero Maximus (played by Russel Crowe) and an all-male band of fighters face at least one chariot borne

gladiatrix (“swordswoman”; pl.

gladiatrices). Even so, it was thought for some time that scenes such as that portrayed in the film and women fighting in the arena were a rare occurrence and dismissed as mere novelty acts.

Ancient voices Yet we know women did perform in the arena as we have several contemporary eyewitness accounts. According to the biographer Suetonius, for example, writing of games held by Emperor Domitian (reigned AD 81 - AD 96) states that women as well as men took part as gladiators (Suetonius, Life of Domitian, 4.1). Around the same time Tacitus informs us that “many women of rank…disgraced themselves in the arena” in gladiatorial games held by Emperor Nero (Tacitus, Annals, 15.32). During a festival in honour of Emperor Nero’s mother, Cassius Dio also notes that women of both senatorial and equestrian rank “drove horses, killed wild beasts and fought as gladiators, some willingly, some sore against their will” (Dio, Roman History, 62.17.3). It should be noted that the involvement of elite women was more of an issue of status rather than gender, as the participation of elite men was shocking as well. In Roman society the upper classes must not entertain lower classes, as the former were at risk of being seen as beneath their observers.

Legislation during the earlier reign of Emperor Augustus is a major clue. It threatened freeborn females with infamia should they participate as gladiators. Much later, around AD 200, Emperor Septimius Severus’ enacted a law forbidding fights between women in Rome’s Flavian Amphitheatre (“The Coliseum”). Significantly, laws are rarely pre-emptive, and historians such as Murray (2003) and McCullough (2008) both agree that legislation in general existed to curb behaviour that was socially unacceptable. In essence, for punishment to be warranted, the crime must have occurred. Both pieces of legislation therefore imply that female gladiators existed.

Sculptural evidence A bronze sculpture from the 1st-century AD (see

right), kept at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbein in Germany, was long thought to be a woman holding a cleaning tool known as a

strigil. In 2011 the statuette was re-evaluated by a Spanish scholar and it now thought she was more likely a female gladiator raising a short, curved sword called a

sica aloft in triumph. Significantly, she is also bare-chested, as gladiators typically fought (Beck, 2022).

One of the best pieces of evidence is in the collection of The British Museum. It is a 2nd-century AD carved marble relief, recovered from Halicarnassus in Türkiye, commemorating either the release from service or the discharge after a draw of two female gladiators named “Amazon” and “Achillia” (see

right). Their stage names are inscribed below each figure on the platform upon which both fighters are standing. At their feet, to each side of the platform, are either the heads of two spectators or the fighters’ helmets. Unfortunately, these objects cannot be positively identified although the latter is favoured as the better explanation given the context. Although missing the head, the figure on the right is the clearest indicator that the two are

gladiatrices as “Achillia” is the female derivation of “Achilles”, the Homeric hero of the “Iliad” [6]. Kathleen Coleman also points out the peculiarity of the women's names as a clear reference to the myth of Achilles and Penthesileia, queen of the Amazons. It could be that this pair of female gladiators often fought each other as a re-enactment of mythological scenes (Coleman, 2000, 487-500).

Both fighters are armed with the same equipment as male gladiators, albeit without helmets, and are advancing to attack with swords and shields. Both are wearing padded leg protection and something similar on their sword arm. Apart from body defences, each figure wears

subligaria, the elaborately folded loincloth held in place with a wide belt (Latin:

balteus). The term

subligaria derives from the verb

subligare meaning “to bind below” (

sub under +

ligare to bind). As shown right, to secure such garments a “long piece of material has to be tied around the waist and then [passed] between the thighs, leaving a section of cloth to emerge at the front, tucking [it] under the knot at the front waist fastening, and out over the crotch area, like an apron” (Shadrake, 2005, 168). Viewed from behind the loincloth has “unflatteringly [been] referred to as a ‘nappy’ or ‘diaper’” (Shadrake, 2005, 168). Most importantly, the wearing of

subligaria accorded with the Italian custom of preserving modesty by covering the genitals.

That said modesty seems have been forgone as, like the aforementioned bronze statuette, each woman’s torso appears to be naked from the waist up. While this seems to have been the case with most categories of gladiator, did women perform topless? If they did, is this one of the reasons gladiatrices were thought of as simply a “titillating spectacle”? Or were Amazon and Achillia depicted bare breasted simply to advertise their gender? Either way, fighting topless in the arena would be impractical and uncomfortable and thus the wearing of a breast band called a strophium [7], as worn by women exercising in the mosaic from Villa Casale, Sicily (pictured below), seems much more likely. The lack of definitive evidence makes it difficult to draw any safe conclusions, however.

Reading the bones Excavations in 2007 identified what scientists believe is the first discovery of an identifiable graveyard for gladiators at Ephesus in Türkiye, once a major city of the Roman world (Deggin, 2015). Marked by three gravestones depicting gladiators, the Ephesus graves yielded thousands of bones from which researchers identified around 67 individuals, mostly aged between 20 and 30 years old. Analysis of their skeletal remains and the injuries present on the bones gave new insights into how the deceased lived, fought and died. Most strikingly was the observation that several “gladiators” bore wounds that had healed during their lifetimes. Apart from being evidence that gladiators were valued enough to received good medical care, it was noted that they had not suffered multiple wounds as might be expected in a melee or close-quarters combat. The observable evidence seemingly proves they fought in organised duels, following rules that were enforced by a referee.

It seems fairly evident that gladiators needed some looking after. For example, we know the Greek physician and philosopher Claudius Galen’s first professional appointment was as a surgeon to gladiators [8]. In AD 157, aged 28, he had returned to Pergamon as physician to the gladiators of the High Priest of Asia. Over his four years in post, he learned the importance of diet, fitness, hygiene, and preventive measures, as well as living anatomy, and the treatment of fractures and severe trauma, referring to their wounds as “windows into the body”. Only five deaths among the gladiators occurred while Galen held the position, compared to sixty in his predecessor's time, a result that is in general ascribed to the attention he paid to their wounds.

We know that gladiators generally fought one-on-one, with armour and weaponry designed to give conflicting advantages. For example, and as previously mentioned, “a lightly armoured, helmetless gladiator with a net and trident, a “retarius”, would typically be matched with a slower moving, more heavily armoured fighter armed with a large helmet, sword and shield” (Deggin, 2015). Most matches employed a senior referee (summa rudis) and one or more assistants, who are often shown in mosaics with long staffs (rudes) to caution or separate opponents at some crucial point in the match. Referees were usually retired gladiators whose decisions, judgement and discretion were, for the most part, respected; they could stop bouts entirely, or pause them to allow the combatants rest, refreshment and a rub-down. The parallels with modern boxing matches divided into rounds and with corner men are inescapable.

Britannia Gladiatorial fights may have begun life as a niche activity at Etruscan funerals, but over the following centuries they were exported to every corner of the expanding Roman empire. Far-flung Britannia was not exempt as evidenced by the physical remains of amphitheatres found in London, Chester, Cirencester, Silchester, Dorchester, and Caerleon. The Colchester Vase [9], dating to AD 175, depicts two gladiators, Memnon and Valentinus (believed to be their stage names) in action. The latter, the

retarius Valentinus, is shown with a raised forefinger indicting his submission to his

secutor opponent, Memnon. An inscription on the vase reads: “Memnon Valentinus of Legion XXX”, who were probably notable local gladiators in their day (the late second century).

For the most part, amphitheatres in Romano-Britain were built by creating turf embankments and digging out the arena. By the early second century, the Cirencester example had been formed by digging out and adapting a quarry on the south-west side of the town. Stone walls were used to create revetments, entrance passageways (

vomitoria, sing. vomitorium), and the arena wall. Dorchester’s amphitheatre was made by adapting a Neolithic henge monument that rather conveniently supplied ready-formed earth embankments around an arena-shaped and sized enclosure. Beneath the Guildhall in London lies its amphitheatre, which once lay close to the fort of the governor of Britannia’s garrison. It is open to the public today. Likewise, visitors can wander around the arena of

Legio II Augusta’s amphitheatre in Caerleon, South Wales. Within the stone-revetted, earthen embankments gladiators would have fought to entertain the garrison’s soldiers and local citizens. They would have sat on wooden benches, long since rotted away, that may have seated 5,000 or 6,000 spectators - enough space for the entire Second Legion. Caerleon’s amphitheatre may have doubled as a venue for speeches to the troops and for formal military exercises or displays.

The Dover Street Woman In 2000, the discovery of the “Great Dover Street Woman” was announced following excavations in 1996 at 165 Great Dover Street, Southwark in London (Bateman, 2008, 194-198). Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) identified the grave of a Romano-British woman dating from the early 2nd- to mid-3rd-century AD. She had received a bustum funeral, a form of cremation above a pit into which her remains eventually fell and were then covered. Although a style of burial rare in Roman Britain, a small amount of human bone survived from which analysis of a pelvis fragment concluded the skeleton was of a female in her 20s. Added to the grave fill after the cremation were eight unburnt ceramic oil lamps and eight tazze [10]. Evidence was also found for molten glass, gold textile, burnt pinecones, chicken, bread, and dates forming part of the cremation ritual (Bateman, 2008, 194-198).

Archaeologists at MOLA proposed that the remains might represent the first female gladiator discovered. The presence of a gladiatorial image on one of the oil lamps, three others showing the Egyptian god Anubis who is associated with the passage of the dead to the underworld, and the style of the burial were suggestive of this interpretation (Bateman, 2008, 194-198). In the 2000 report of the excavations by MOLA, Angela Wardle concluded that while the interpretation of this cremation as a gladiator “can only be speculative...it is certainly possible” (Wardle, 2000, 27-30). This interpretation is contested because the excavated evidence is far too speculative. As Alexandra Sills points out: “attempts to identify the remains of Roman women as gladiators, such as the Great Dover Street lady of London, are often influenced by the desire for a good story rather than conclusive material evidence” (Sills, 2021). Sadly, in an era where funding for archaeological work is tied inextricably to headline grabbing public relations, one can see why such a tenuous gladiator connection was seized upon. Without further conclusive proof perhaps Nick Bateman is right to conclude that the burial was more likely to represent a complex religious and ritual process which incorporated gladiatorial images rather than representing the life experience of the woman as a gladiator (Bateman, 2008, 194-198). Perhaps the final word on gladiatrices should go to Susanna Shadrake, author of “The World of the Gladiator”, who points out: “the subject of female gladiators has always aroused strong emotions; then as now, they have been seen as aberrations or novelties” (Shadrake, 2005, 185). As mentioned previously, there are a few references to women fighters in the literary sources, and some evidence from inscriptions on monuments. From such evidence it is reasonable to say

gladiatrices clearly existed “as an authentic gladiatorial category rather than a fevered fantasy” (Shadrake, 2005, 185). Such proof of their existence however does not guarantee how frequently women appeared in the arena.

We have only briefly touched the subject of gladiators, but hopefully we have dispelled three of the common misconceptions or myths about them. Not everyone who entered the arena began life as a slave, although volunteering to do so invited a form of public disgrace. Both men and women fought but not always to the death as movies might lead us to believe. That is not to say it was a life without risk as all combat is inherently dangerous. Yet one cannot help wondering whether it is the thrill of the dangers that continues to attract audiences to this day.

References:

Bateman, N., (2008), “Death, women, and the afterlife: some thoughts on a burial in Southwark”, in John Clark; Jonathan Cotton; Jenny Hall; Roz Sherris; Hedley Swain (eds.), “Londinium and Beyond: Essays on Roman London and its Hinterland for Harvey Sheldon” (PDF), CBA Research Report 156, Council for British Archaeology.

Coleman, K., (2000), “Missio at Halicarnassus”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 100.

McCullough, A., (2008), “Female Gladiators in Imperial Rome: Literary Context and Historical Fact”, The Classical World 101:2, pp. 197-209.

Murray, S. R., (2003), “Female Gladiators of the Ancient Roman World”, The Journal of Combative Sport, July Issue, pp. 1-16.

Shadrake, S. (2005), “The World of the Gladiator”, Stroud: Tempus.

Wardle, A., (2000), “Funerary rites, burial practice and belief”, in Mackinder, A. (ed.), ‘Romano-British Cemetery on Watling Street: Excavations at 165 Great Dover Street, Southwark, London’, MOLA Studies Series 4, Museum of London Archaeology.

Ancient sources:

Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 62.

Suetonius, Life of Domitian.

Tacitus, Annals, Book 15, 1-32.

Endnotes:

1. Munera were public works and entertainments provided for the benefit of the Roman people by individuals of high status and wealth. Munera (sing. munus) means “duty, obligation” in the sense that an individual had a responsibility to provide a service or contribution to his community. The word was often a synonym for gladiatorial combat, which was originally sponsored as a funeral tribute at the tomb of a deceased Roman magnate by his heir. Munera depended on the private largesse of individuals, in contrast to ludi, which were games, athletic contests or spectacles sponsored by the state.

2. Gladiators’ value as entertainers was commemorated in precious and commonplace objects throughout the Roman world.

3. In ancient Roman society, infamia (in-, “not”, and fama “reputation”) was a loss of legal or social standing; in effect public disgrace. In Roman law a censor or praetor could impose infamia whereby a person was officially excluded from the legal protections enjoyed by a Roman citizen. More generally, especially during the Republic and Principate, infamia was informal damage to one's esteem or reputation. Such a person was known as an infamis (pl. infames).

4. Latin palus, meaning “stake” or “post”, is probably a reference to the post erected in ludi for gladiators, or in army training grounds for soldiers, to practice sword cuts and thrusts.

5. Mixed martial arts (MMA) is a full-contact fighting sport based on striking and grappling, incorporating techniques from various combat sports from around the world. In line with other professional wrestling promotions, WWE shows are not true contests but entertainment-based performance theatre, featuring storyline-driven, scripted, and partially choreographed matches. The more theatrical nature does not belie that WWE matches often include moves which can put performers at risk of injury, even death, if not performed correctly.

6. The epic poem recounting the tale of the Greek siege of Troy.

7. Also known as fascia pectoralis, fasciola, taenia, or mamillare.

8. Considered to be one of the most accomplished of all medical researchers of antiquity, Galen influenced the development of various scientific disciplines, including anatomy, physiology, pathology, pharmacology, and neurology, as well as philosophy and logic. His understanding of anatomy and medicine was principally influenced by the then-current theory of the four humours, namely black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm. Galen's views dominated and influenced Western medical science for more than 1,300 years.

9. The Colchester Vase was discovered in a Roman-era grave in 1853, which held the deceased's cremated remains. Renowned as one of the finest pieces of Roman-British pottery in existence, it is currently part of the Colchester Castle Museum collection.

10. A tazza (pl. tazze) is a wide but shallow saucer-like dish either mounted on a stem and foot or on a foot alone. The word has been generally adopted by archaeologists and connoisseurs for this type of vessel, which is used either for drinking, serving small items of food, or just for display. Tazze are commonly made in metal, glass, or ceramics, but may be made of other materials.