Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a tree, stake, beam or large wooden cross, and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by, among others. the ancient Greeks, Persians, Carthaginians and the Romans. Supposedly one of the keenest practitioners of crucifixion historically, to the Romans crucifixion was a punishment reserved for slaves or the worst kind of criminals, particularly those who threatened the status quo or challenged Rome’s authority. When, for example, the slave revolt led by the former gladiator Spartacus was finally suppressed, contemporary accounts claim 6,000 prisoners were duly crucified along the Via Appia between Capua and Rome. Such a visible punishment was clearly intended as an abject lesson to any slave tempted to flee from or kill their master that they would suffer the same fate.

Crucifixion is said to have evolved from the Assyrian, and later the Persian, preference for impalement as a means of execution where the criminal was transfixed by a pointed stake passing longitudinally through the body. The two methods are not truly comparable, however, even though in both methods some form of a stake (Latin stipes) was used, and victims were not subjected to a prolonged and painful death. It is from the Roman writer Seneca’s [1] De Consolatione ad Marciam (“On Consolation to Marcia”), written around AD 40, that we learn crucifixion and impalement are two distinct kinds of execution:

Video istic cruces ne unius quidem generis sed aliter ab aliis fabricatas; capite quidam conuersos in terram suspendere, alii per obscena stipitem egerunt, alii brachia patibulo explicuerunt; video fidiculas, video uerbera...“I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made differently by different [fabricators]; some individuals suspended their victims with heads inverted toward the ground; some drove a stake (stipes) through their excretory organs/genitals; others stretched out their [victims'] arms on a patibulum [cross bar]; I see racks, I see lashes...”

(Seneca, Cons. ad Marc. XX)

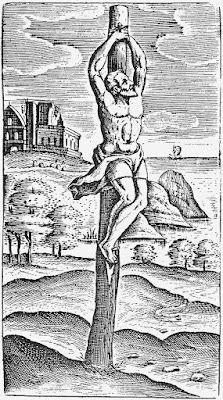

Unlike the Assyrians and Persians, impalement was the less usual Roman method. Rather, it seems public crucifixion was preferred with the condemned typically suspended from a tree, a wooden stake, or some form of wooden cross (Latin crux). The familiar T-shaped cross, however, was not necessarily the most common method used. Rather an X-shaped construction made of two pieces of wood crossed to form four right angles, known as a Saltire, was more widespread, as was a single upright post or tree (Latin: crux simplex or stipes) to which the condemned would be tied or nailed either facing forward or backward. Interestingly, Seneca notes that some victims were suspended “with heads inverted toward the ground”. Possibly the most famous example of this was the execution of the apostle Simon Peter (later Saint Peter), at least in the Christian tradition.

St Peter One of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus, and one of the first leaders of the early Christian Church, the Roman authorities sentenced Peter to death by crucifixion. Somewhat inconveniently, however, the details of his execution are not described in Scripture. Despite this, numerous writers at the time (or shortly thereafter) claim Peter was martyred for his faith in Rome sometime shortly after the Great Fire in AD 64. The same early Church tradition also claims Emperor Nero wished to blame the Christians for the disastrous fire that had destroyed large swathes of the city. Echoing Seneca observation above, in accordance with his eponymous apocryphal Acts, Peter asked to be crucified head down as he felt unworthy to die in the same manner as Jesus. Significantly, the Jewish historian Josephus informs us that, in the first century AD, Roman soldiers had delighted in nailing Jewish rebels to crosses in different humorous poses. It is likely that the author of the Acts of Peter would have known this and the position attributed to Peter's crucifixion is thus plausible, either happening historically or invented by the aforementioned author of the Acts.

Manner of execution The criminal, after sentence was pronounced, carried his cross to the place of execution. According to William Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities under the entry for “crux” (“cross”) both Plutarch (De Tard. Dei Vind. ἕκαστος τῶν κακούργων ἐκφέρει τὸν αὐτοῦ σταυρόν), Artemidorus (Oneir. II.61) as well as the Gospels mention this practice. Smith also notes, from Livy (XXXIII.36) and Valerius Maximus (I.7), that the Romans, as with other capital punishments, would often scourge the condemned before their crucifixion. Stripped of their clothes, the criminal was taken to the place of execution and there nailed or bound to the cross. Binding was the more painful method as it prolonged suffering leaving the condemned to die of hunger. Instances are recorded of the crucified surviving nine days. It was usual to leave the body on the cross after death. Of note, the deliberate breaking of the legs of the thieves mentioned in the Gospels was not the normal practice. That this happened was most likely to hasten death given that Jewish law expressly demanded bodies of the condemned could not remain on the cross during the Sabbath-day.

Physical evidence? Despite contemporary Roman authors recording thousands of victims being crucified throughout the Roman Iron Age there has been little archaeological evidence to shed light on how it was performed. In popular western consciousness, our understanding of the practice has been heavily influenced by Christian iconography and the Gospels. This should come as no surprise as the most famous example of crucifixion, certainly within Europe and its subsequent sphere of influence, is the execution of Jesus in Roman-controlled Judaea [2]. His gruesome and public death followed by his subsequent resurrection was, and remains, the foundation of Christian beliefs.

Although not the most common form of cross, as previously mentioned, that represented by the letter T - the Tau cross - had been adopted as a symbol of Early Christianity by the 2nd-century AD. The use of the more familiar Greek and Latin crosses (as pictured) with intersecting beams appear in Christian art towards the end of Late Antiquity (from the late 3rd-century to the 7th- or 8th-century in Europe). While we cannot say with any certainty which form of cross was used - remember the most common form was the Saltire or possibly Tau versions - representations of the crucifixion can be found in most Christian churches. These ubiquitous depictions nearly all show Jesus with nails driven through his feet and the palms of his hands - the stigmata of the Christian tradition. As shown above, Caravaggio’s [3] iconic depiction of the “Crucifixion of Saint Peter” of 1601, which hangs in the Cerasi Chapel of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, is a good example of crucifixion as portrayed in Renaissance art. Apart from the atypical upside-down attitude of Saint Peter, viewers will note that a single large nail is shown driven through each hand and each foot.

Ignoring the feet for a moment, depicting a nail pinioning each hand to a cross-beam (patibulum) derives from the description of Jesus’ wounds where the Greek word ‘χείρ’ used in the Gospel of John (20:25) has been traditionally translated as ‘hand’. Unfortunately, like so many other words with multiple meanings, χείρ could also refer to the entire forearm below the elbow. It has thus become popular to contend that the nails were inserted just above the wrist, through the soft tissue, between the two bones of the forearm (the radius and the ulna). While nails are almost always depicted in religious art, historically we know the Romans sometimes just tied victims to the cross. So, were victims tied or nailed to a gibbet, whether that was a tree, a stake or a cross? More worryingly, if the Romans crucified 1,000s of people as is so often stated, why is there such a lack of archaeological evidence?

A little piece of evidence The small discovery of a nail, just a few millimetres long, hammered through a skeleton’s heel was hailed as both the best evidence yet of Roman crucifixion and the first example of its kind found in Britain [4]. The nail remains embedded in the right heel and ankle of a man who was aged in his mid to late thirties at the time of his death. The remains, dating to about AD 250, were found in a previously unknown settlement in the Cambridgeshire village of Fenstanton. Twelve other nails were also located about the skeleton perhaps indicative of the deceased being carried to his grave on a stretcher-like wooden board. Experts theorise that the man had been crucified since the mode of carriage would have been useful in cases where a corpse had been left to decompose on the cross (a sobering thought).

Little is known about the individual but given crucifixion was banned for citizens at the time, but not for members of the lower classes, rebels and slaves, implies the remains may be those of a slave (Ingham & Duhig, 2022, 18-29).

The case from archaeology There are only three other known possible examples of Roman era crucifixion from Jerusalem, Italy and Egypt respectively. Although the ancient historians Josephus and Appian refer to the crucifixion of thousands of Jews by the Romans, there is only a single archaeological discovery of a crucified body of a Jew dating back to the Roman Empire around the time of Jesus. Discovered at Giv’at ha-Mivtar in northeast Jerusalem in 1968 (Tzaferis, 1970, 18-32), the remains included a heel bone (calcaneum) with a nail driven through it as pictured. This crucial piece of evidence was accidently found in an ossuary with a man's name inscribed on it that translates as “Jehohanan, the son of Hagakol” (Haas, 1970, 38-59; Tzaferis, 1985, 44-53; Zias, 1985, 22-27). Assigning this particular name to the person’s remains can be argued is no more than an assumption that, if we are truly critical, probably cannot be independently corroborated. Yet, while it is perfectly reasonable to assume the most likely explanation is that the bones are those of “Jehohanan”, what if the bones were placed in a re-used ossuary with the previous occupant’s name still scratched into its surface? An element of doubt means we cannot be completely certain but on the balance of probability, the name inscribed on the ossuary and the remains within are most likely synonymous. “Jehohanan, the son of Hagakol” is, for now, our single known Jewish victim of crucifixion.

Returning to the archaeological evidence, Nicu Haas, an anthropologist in the Department of Anatomy at the Hebrew University Medical School in Jerusalem, was the first to examine the ossuary and Jehohanan’s remains in 1970. The initial account of the length of the nail led Haas and others to conclude:

“The feet were joined almost parallel, both transfixed by the same nail at the heels, with the legs adjacent; the knees were doubled, the right one overlapping the left; the trunk was contorted; the upper limbs were stretched out, each stabbed by a nail in the forearm.”

(Israel Exploration Journal, Vol-20, 1970)

Interestingly, ancient sources mention the sedile, a small seat attached to the front of the upright, about halfway down, which could have served to take the person's weight off the wrists. A footrest (suppedaneum) attached to the upright perhaps for a similar purpose, is sometimes included in representations of Jesus’ crucifixion but, interestingly, is not discussed in ancient sources.

Haas’ conclusions became widely accepted by the public, but several errors in his observations were later identified. In 1985, Joe Zias, curator of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums, and Eliezer Sekeles from the Hadassah Medical Centre, re-examined the crucifixion remains. They determined the initial measurement of the nail was inaccurate being shorter than Haas had reported. Its true length, 11.5 cm (4.53 inches), would not have been long enough to pierce two heel bones and the wood. Moreover, pieces of bone had been misidentified, some bone fragments were from another individual and, significantly, there was no bone from a second heel. In other words, the nail had pierced only one heel so Jehohanan’s two heels may not have been nailed together. In the absence of the second heel, which may or may not have been pierced by a nail, one might surmise that his heels could have been nailed separately to either side of the upright post (Chapman, 2008, 86-89; Zias, 1985, 22-27; Zias, 2004). Whichever way his feet were secured, to hasten the man’s death, his legs had been broken perimortem, but remember this is atypical for a Roman crucifixion as described above.

So far in all cases, Jerusalem, Italy and Fenstanton, only one heel bone transfixed with a nail have been recovered. Based on this slender evidence it has been assumed, not unreasonably, that both heels were [probably] nailed to the wooden upright, but might this be wrong? Whether or not the victim was nailed or bound to a patibulum crossbeam, what if only one heel needed to be transfixed to secure them to the upright? With their arms pinned, it is highly unlikely that the condemned could easily free their feet, and if they did, how would that serve to save them? Indeed, it might even serve to speed their demise, something the authorities would not be keen to happen. So, while it is probably unwise to extrapolate too much from these two finds, might they indicate the Romans were content that one heel bone pierced by a single nail was sufficient guarantee of security. And while it pains the author to say it, the bureaucratic Roman army might see using one less nail as being more efficient and (here is an awful thought) a cost saving measure.

Hand or wrist? Further examination determined olive wood fragments were adhered to the point of the nail thus indicating that Jehohanan was probably crucified on a cross made of olive wood or more likely on an olive tree. However, as pictured olive trees do not grow nice and straight so manufacturing the archetypal cross of two intersecting straight beams becomes far more laborious and time-consuming. The tip of the nail was bent, possibly from striking a knot in the wood, which prevented it being extracted from the foot. In addition, a piece of acacia wood was found between the bones and the head of the nail. It is presumed that, where nails were used to crucify the condemned, these pieces of wood prevented the victim or their own body weight pulling the nail through the feet (or wrists).

Haas examination also identified a scratch on the inner surface of the right radius bone of the forearm, close to the wrist. He deduced from the form of the scratch, as well as from the intact wrist bones, that a nail had been driven into the forearm at that position. Along with many of Haas' findings, however, his conclusions have been challenged as it was subsequently determined by Zias and Sekeles that the scratches in the wrist area were non-traumatic and, therefore, not definitive evidence of crucifixion:

“Many non-traumatic scratches and indentations similar to these are found on ancient skeletal material. In fact, two similar non-traumatic indentations were observed on the right fibula, neither are connected with the crucifixion...Thus, the lack of traumatic injury to the forearm and metacarpals of the hand seems to suggest that the arms of the condemned were tied rather than nailed to the cross.”

The findings of Zias and Sekeles could not conclude whether in this case a horizontal patibulum crossbeam was attached to the upright stake to which the victim's heel was nailed. The evidence was so ambiguous concerning the victim’s arms that Zias and Sekeles had to rely on the data provided by contemporary writings to support their reconstruction of the position of the arms as attached to a crossbeam. Yet while contemporary Roman literary sources contain numerous descriptions of crucifixion, they say little about how the condemned were affixed to the cross. Unfortunately, as with the Fenstanton find, the direct physical evidence from Jerusalem is limited to one right heel calcaneum (heel bone) pierced by an 11.5 cm iron nail with traces of wood at both ends.

The end is nigh Crucifixion was intended to be a gruesome spectacle leading to a painful and humiliating death. As stated, it was originally reserved to punish slaves, pirates and enemies of the state, the latter presumably being the category in which Jesus found himself condemned. As a capital punishment crucifixion was not applicable to Roman citizens until it was later extended to those of the lower classes (humiliores) [5].

The length of time it might take for a victim to die could range from hours to days depending on their health, the prevailing environment and which method of crucifixion was used. In 1950, Pierre Barbet theorised that, when the whole body weight was supported by the stretched arms, the typical cause of death was asphyxiation. The victim’s weight would cause hyper-expansion of the chest muscles and lungs making it difficult to breath. The only way to alleviate this would be for the victim to draw himself up by the arms to relieve the pressure, possible aided by his feet being supported by tying or resting on a wood block (suppedaneum). Regardless, the effort needed would quickly lead to exhaustion only for the body to sag once more. Over time the two sets of muscles used for breathing, the intercostal muscles and the diaphragm, would become progressively weakened. This cycle might continue until the victim is no longer able to lift himself leading to death within a few minutes. While Babet’s theory has been supported by several scholars (Habermas, Kopel & Shaw, 2021, 748–52), the medical consensus is that asphyxia is unlikely to be the primary cause of death by crucifixion (McGovern, Kaminskas & Fernandes, 2023, 64–79).

Several other possible causes of death (Maslen & Piers, 2006, 185–188) have been mooted. These include heart failure or arrhythmia (an abnormal heart rhythm) (Edwards, Gabel & Hosmer, 1986, 1455–1463; Davis, 1962, 182), hypovolemic shock caused by the loss of too much blood or fluid (Zugibe, 2005), acidosis leading to excess acid in the body fluids (Wijffels, 2000, 52 (3)), dehydration (Retief & Cilliers, 2003, 938–941), and pulmonary embolism, a blocking of an artery in the lungs (Brenner, 2005, 1–2). Any one of these factors or a combination of them, or indeed many other causes will most likely result in death.

Conclusion In reconstructing any crucifixion reliance has to be placed on the limited skeletal evidence together with the observations made by Haas, Barbet et al. and the ancient historical sources. Despite that the most common of crucifixions used either a simple stake (stipes) or a tree, modern reconstructions usually include a crossbeam (patibulum). According to the ancient sources, the condemned man never carried the complete cross, as is commonly believed. Rather, only the crossbeam was carried, while the upright was set in a permanent place where it was used for subsequent executions. Usefully therefore the same crossbeam could be used repeatedly for attachment to an upright stake permanently fixed in the ground. Moreover, Josephus tells us that during the first century AD, wood was so scarce in Jerusalem that the Romans were forced to travel ten miles from the city to secure timber for their siege machinery. If wood was so scarce, it makes sense, at the very least economically, for the crossbeam and upright to be used repeatedly.

Literary and artistic evidence seems to suggest that the arms of the condemned were tied with ropes rather than nailed to the cross. Even so, it must be borne in mind that death by crucifixion resulted from the manner in which the condemned person hung from the cross and not any traumatic injury caused by nailing. Hanging from the cross resulted in a painful process of asphyxiation until the condemned person expired, unable to continue breathing properly.

References:

Arkeonews, (2021), ‘First example of Roman crucifixion in UK discovered in Cambridgeshire village’, available online (accessed July 13th, 2022).

Brenner, B., (2005), ‘Did Jesus Christ die of pulmonary embolism?’, J Thromb Haemost, 3 (9), pp. 1–2.

Chapman, D.W. (2008), ‘Ancient Jewish and Christian perceptions of crucifixion’, Baker Academic.

Davis, CT (1962). "The Crucifixion of Jesus. The Passion of Christ From a Medical Point of View". Arizona Medicine. 22: 182.

Edwards, W.D., Gabel, W.J. & Hosmer, F.E., (1986), ‘On the physical cause of death of Jesus Christ’, Journal of the American Medical Association, 255 (11), pp. 1455–1463.

Habermas, G., Kopel, J., & Shaw, B.C.F., (2021), ‘Medical views on the death by crucifixion of Jesus Christ’, Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 34 (6), pp. 748–52.

Granger Cook, J., (2014), “Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World”, Mohr Siebeck.

Gualdi-Russo, E., Thun Hohenstein, U., Onisto, N. et al., (2019), ‘A multidisciplinary study of calcaneal trauma in Roman Italy: a possible case of crucifixion?’, Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11, 1783–1791, available online (accessed July 13th, 2022).

Haas, N., (1970), ‘Anthropological observations on the skeletal remains from Giv'at ha-Mivtar’, Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1/2, pp. 38-59, available online (accessed June 23rd, 2023).

Ingham D., Duhig C., (2022), ‘Crucifixion in the Fens: life & death in Roman Fenstanton’. British Archaeology, January-February 2022, available online (accessed July 13th, 2022).

Maslen, M. & Piers D.M., (2006), ‘Medical theories on the cause of death in crucifixion’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99 (4), pp. 185–188.

McGovern, T.W., Kaminskas, D.A. & Fernandes, E.S., (2023), ‘Did Jesus Die by Suffocation? An Appraisal of the Evidence’, Linacre Quarterly, 90 (1), pp. 64–79.

Retief, F.P. & Cilliers, L., (2003), ‘The history and pathology of crucifixion’, South African Medical Journal, 93 (12), pp. 938–941.

Smith W., D.C.L., LL.D., (1875), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, “Crux”, London: John Murray, available online at “LacusCurtius” (accessed April 15th, 2024).

Tzaferis, V., (1970), ‘Jewish Tombs at and near Giv'at ha-Mivtar’, Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1/2, pp. 18-32, available online (accessed June 23rd, 2023).

Tzaferis, V., (1985), ‘Crucifixion - The Archaeological Evidence’, Biblical Archaeology Review 11, Available online (accessed June 23rd, 2023).

Wijffels, F., (2000), ‘Death on the cross: did the Turin Shroud once envelop a crucified body?’, Br Soc Turin Shroud Newsletter, 52 (3).

Zias, J. and Sekeles, E., (1985), ‘The Crucified Man from Giv'at Ha-Mivtar: A Reappraisal’, Israel Exploration Journal 35 (1), pp. 22-27, Available online (accessed June 23rd, 2023).

Zias, J., (2004), ‘Crucifixion in Antiquity - The Anthropological Evidence’, COJS.org, Available online (accessed July 13th, 2022).

Zugibe, F.T., (2005), ‘The Crucifixion Of Jesus: A Forensic Inquiry’, New York: M. Evans and Company.

Endnotes:

1. Lucius Annaeus Seneca [the Younger] (c. 4 BC – AD 65) was a Stoic philosopher of ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

2. The crucifixion of Jesus occurred in 1st century Judaea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, and is attested to by other ancient sources. Consequently, it is considered an established historical event, although there is no consensus among historians on the details.

3. Michelangelo Merisi (or Amerighi) da Caravaggio (more popularly known simply as Caravaggio) was born on September 29th, 1571 in Milan, Italy. He died aged 38 on July 18th, 1610 in Porto Ercole in Tuscany, Italy.

4. BBC History Magazine (February 2022), ‘History in the News: Evidence of Roman crucifixion found in UK’, p. 8.

5. The most common punishment for a Roman citizen was a fine (damnum). Thieves would have to pay compensation many times higher than the value of the stolen item(s) and would be deemed infamous (ignominia). Citizens might deny lawbreakers access to fire and water, and anyone legally banished from Roman society (exilium) forfeited all their privileges and property. While citizens could be condemned to a life of slavery (servitus), Roman law determined the death penalty only applied if they had committed treason or patricide. Roman citizens were thus very rarely sentenced to death, and in all instances a citizen could not be crucified. Wealthier persons and the Roman elite guilty of capital crimes were most likely to be executed by the sword, either self-inflicted (suicide) or beheaded by an executioner.

6. Sepsis, sometimes called septicaemia or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening overreaction by the immune system to an infection that starts to damage your body's own tissues and organs. You cannot catch sepsis from another person.

_Captioned.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment