Foreword

In

his original foreword, Clive duly thanked Dr Jane Malcom-Davies and Caroline

Johnson, both of The Costume Society, Katrina Bill of The Textile Society, Dr

AT Croom from Arbeia Roman Fort, and the librarians of his local library for

the invaluable help they all provided.

Despite a decade passing, the information they generously supplied still

forms the basis of this paper. It seems

appropriate that Clive’s acknowledgements should echoed here.

Clive

was often never happy with the result of his efforts and thus reluctant to

publish. I have, however, taken the

decision to do so with an updated version for today’s web based media. The research and information contained

therein remains firmly Clive’s intellectual property. Any mistakes or deviations from Clive’s

original intention are purely my own.

Mark Hatch, Staffordshire

2017

Introduction

Ask most people to describe a Roman toga (pl. togae) and

images from popular film and television will dominate. The prevailing picture

tends to be of a white cloth sheet or wool blanket casually draped over one

shoulder that can be shrugged on and off with ease. For good reason, the ‘Hollywood’ toga

is in a class of its own. The

distinctive garment of ancient Rome, however, had a much more complex nature,

and was imbued with symbolic meaning.

In essence, however, the toga was invariably made of wool cloth[1]

of varying sizes up to six metres (20 inches) in length that was wrapped around

the body. It was generally worn over a tunica, a universally worn

garment often confused and misidentified as a toga. After the 2nd

century BC, the toga was worn almost exclusively by men, and only by

Roman citizens. While in earlier times women had also worn the toga,

from the 2nd century BC onward they were expected to wear the stola.

History

To most people the toga is quintessentially Roman, but in fact it

was derived from a robe worn by the native Etruscans, a people who had lived in

Italy since ca. 1,200 BC. The tebenna,

as it was known, was merely an oblong of cloth worn as both a tunica and

a blanket. Etruscan farmers would wear

the tebenna when working in their

fields, or as their “battle dress” when drafted into the army. It was only much later that this garment metamorphosed

into the toga, a formal dress item that, oddly, seemed to have been much

despised and never a popular thing to wear.

The toga is believed to have been adopted around the time of Numa

Pompilius, the second King of Rome. The

garment was taken off indoors, or when hard at work in the fields, but it was

considered the only decent attire out-of-doors. The story of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus

(see inset) epitomises the toga’s status in Roman society. As the story

goes, a group of Senators were sent to tell Cincinnatus that he had been

nominated dictator. According to Livy,

they found Cincinnatus ploughing a field on his farm. The delegation asked him to put on his

senatorial toga before hearing the mandate of the Senate and Cincinnatus

duly called for his wife to bring his toga

from their cottage. Once dressed he was

hailed dictator and told to come to the city.[2] While the truth of the story may be doubtful,

it nevertheless expresses the Roman sentiment that the toga was the

appropriate dress for formal and ceremonial occasions.

Over time dress styles change. The

Romans, for example, adopted the tunica (pl. tunicae) from their Greek and Etruscan neighbours (Gr: chiton).

Tunicae were simply long tubes of

cloth sewn together, with holes left unsewn for the arms and head; later, it

became fashionable for tunicae to be made with sleeves. In time the Roman toga became bulkier and the fashion was for it to be worn in a

looser manner over the tunica. The result was that the toga became impractical for active daily pursuits, such as those of

farming or war. Indeed, in times of war,

its place was taken by the handier sagum (a rectangular woollen cloak),

and in times of peace the toga was superseded by the laena, lacerna,

paenula, and other forms of buttoned or closed cloaks. From the simple blanket and ‘battle dress’ of

the Etruscan and early Latin kings period, the toga had become a symbol

of peace and, perhaps most importantly, citizenship.[3]

The Republican Toga By the 2nd century BC, the toga

had, with two exceptions, become an item of purely male dress. It had a rounded lower edge and a small

over-fold (sinus) at the top.

Being worn over a mid-calf length tunica, this form of toga

seems to have continued in use well into the Imperial period.

Late 1st to early 2nd century AD During this period the toga developed

into a much larger garment. At some five

metres it could no longer be put on alone, and the wearer needed at least two

others to help don the garment. To cater

for this the shape changed to a roughly trapezoidal form for the sinus

area over a semi-circular form at the bottom.

Writing in the late 1st century AD, Quintillion goes

to some length on the correct way for an orator to wear one:

“In

my opinion the Toga should be rounded and cut to fit if it is not to be

unshapely. The front edge should reach

the middle of the shin whilst the back should be somewhat higher...the sinus

should fall to a little above the edge of the tunica if it is to be the

most becoming, it should not fall below it.

That part that passes like a belt from under the right arm to over the

left shoulder should be neither too tight nor too loose. The portion that is last to be arranged

should sit rather low, since it will sit better thus and may be kept in place. A part of the tunica should be drawn

back in order that it may not fall over the arm when we are pleading, and the sinus

should be thrown back over the shoulder, while it will not be unbecoming if the

edge is turned back.”

Early 2nd to early 3rd century AD There seem to have been some relatively minor

changes to the way the toga was worn, with the sinus becoming longer -

further towards the calf than previously.

From Trajanic reliefs it seems that the fold coming under the right arm

and the over the left shoulder (balteus) was folded tighter after AD

119. The umbo also became

exaggerated by an increase in its overall length.

Early to late 3rd century AD The balteus became grossly

exaggerated; it was concertina-folded to form a smooth band and was taken twice

around the body. A great deal of

practice is needed to prepare the balteus to meet the required fashion.

Early 4th century AD While the style with an exaggerated balteus

continued, the sinus also grew so baggy that if not held on the right

arm it swept the ground.

Late toga After the “fall” of the Western Empire the toga

slowly changed to a shape akin to a “Yale” type of key. It must have been easier to put on, cost less

and was easier to wear.

Modern Usage In several countries, "toga parties" remain a popular entertainment, especially in colleges and universities. Taking their lead from films such as Animal House, where exaggerated tales of Roman debauchery are clearly the inspiration, participants usually don makeshift garments fashioned from bedsheets. Clearly, such "togas" bear little resemblance to the Roman garment, being both flimsier and scantier.

Significance

The same process that removed the toga from everyday life gave it

an increased importance as a ceremonial garment. As early as the 2nd century BC, and

probably even before, the toga (along with boots known as calceus)

was looked upon as the characteristic badge of Roman citizenship; wearing the toga was denied to foreigners[4]

and to exiled Romans.[5] On

the other hand, it was worn as badge of office by magistrates on all occasions.

In fact, for a magistrate to appear in a Greek cloak (pallium) and

sandals was considered by all as highly improper, if not criminal.l[6] The Emperor Augustus, for instance, was so

incensed at seeing a meeting of citizens who were not wearing their togae, that, quoting Virgil's proud

lines, "Romanos, rerum dominos, gentemque togatam"

("Romans, lords of the world, the toga-wearing race"), he gave orders

to the aediles that in the future no one was to appear in the Forum or

Circus without it[7].

Because the toga was not worn by soldiers, it was regarded as a

sign of peace. A civilian was sometimes called togatus,

"toga-wearer", in contrast to paenula or sagum-wearing

soldiers. Cicero's De Officiis

contains the phrase cedant arma togae: literally, "let arms yield

to the toga", meaning "may peace replace war", or "may

military power yield to civilian power."

The toga‘s ceremonial role is exemplified

when worn during religious rites. Those who

officiated in sacred rituals, but who not part of the formal priesthood, wore

the toga “Capite Velato“ where

the sinus was pulled up to cover the head (priests wore special pointed hats

known as apex). Occasions where this might occur, for example,

include weddings, funerals and state occasions. The depictions on the Ara Pacis Augustae

show little conformity on who wore the toga covering the head. It seems that only those immediately around

the altar did so but where the distinction was drawn remains unclear.

Varieties

Bunsen describes[8] the toga as: “Essentially a white

woollen cloth, cut to a semi-circular design, some five yards long and four

yards wide, varying according to the size of the wearer. Part of it was pressed, and possibly sewn,

into plaits and doubled lengthwise so that one of the folds (sinus)

would fit comfortably around the hip and chest whilst allowing room enough to

walk or move.” The description appears to be of the early Republican toga

as those of the later Imperial period where considerably longer and fuller,

between four metres and six metres long and up to three metres wide depending

on the size of the wearer and how full a toga was desired. At the height of the Empire, a toga

could be seven to eight metres long and thus would require gathering, pinning

or tying in an umbo (boss) at the left shoulder to make the garment more

manageable.

As the garment evolved almost all the major differences were in size,

ornamentation and colour. Contemporary

descriptions refer to purple togae being reserved for the Imperial

family, dark coloured togae for plebeians and for those in mourning, and

the embroidered “toga picta” for those celebrating a triumph. References to the actual material are rarely

mentioned, although Ovid notes togae were made from very thin or

translucent fabrics and Varro states that the tunic’s purple stripe (clavus)

could be seen through the toga. Similarly,

Suetonius castigates the wearing of “cloaks of outlandish colours” and

something he called a “transparent toga”.

Indeed, there were many kinds of togae. Each was used differently, some to distinguish

social status and others for ceremonial purposes. The following examples

represent those togae most often referred to in literary sources and

from which we can determine their style and use:

·

Toga virilis (toga

alba or toga pura): A plain toga worn on formal occasions by

most Roman men of legal age, generally from about 14 to 18 years, but it could

be any stage in their teens[9].

The first wearing of the toga virilis was part of the

celebrations on reaching maturity. Made

of off-white or greyish wool depending on the natural colour of the sheep’s

fleece. Bleaching (by “fulling”) would

have whitened the toga but is unlikely to have produced a “pure white”

as its alternative names might imply.

·

Toga candida:

"Bright toga"; a toga bleached by chalk to a dazzling

white (Isidorus Orig. xix. 24, 6), worn by candidates for public office.[10]

Oddly, this custom appears to have been

banned by plebiscite in 432 BC, but the restriction was never enforced.[11]

The term is the etymologic source of the

word candidate.

·

Toga praetexta: An

ordinary “white” toga with, if you were of the appropriate social class,

a broad reddish-purple stripe woven or sewn on its border. Originally the stripe was on the lower edge

of the toga until moved to the edge of the sinus. The toga

praetexta was worn by:

·

Freeborn boys who had not yet come of age (majority).[12]

Until the late 1st century

AD, when girls stopped wearing it, young boys and girls of respectable families

could wear the toga praetexta until the boys’ majority or the girls

married.

· All curule magistrates.[13][14]

·

Ex-curule magistrates and dictators, upon burial[15]

and apparently at festivals and other celebrations as well.[16]

·

Some priests (e.g.,

the Flamen Dialis, Pontifices, Tresviri Epulones, the

augurs, and the Arval brothers).[17]

·

Those of senatorial rank wore a toga praetexta with

“a broad crimson stripe" (latus clavus) 75 mm (3”) wide. A narrower stripe (augustus clavus) of

25 mm (1”) wide was reserved for those of Equestrian rank.

·

During the Empire, the right to wear it was sometimes

bestowed as an honour independent of formal ran

·

According to tradition, the Kings of Rome.

·

It also gave its name to a literary form known as praetexta.

·

Toga pulla:

Literally “dark toga”. It was

worn mainly by mourners, but could also be worn in times of private danger or

public anxiety. It was sometimes used as

a protest of sorts - when the orator and ex-Consul Marcus Tullius Cicero was

exiled, the Senate resolved to wear togae pullae as a demonstration

against the decision.[18] Magistrates

with the right to wear a toga praetexta wore a simple toga pura

instead of pulla.

·

Toga picta:

The toga picta, unlike all others, was decorated with a red stripe with

gold embroidery. Under the Republic, it

was worn by generals in their triumphs, and by the Praetor Urbanus when

he rode in the chariot of the gods into the circus at the Ludi Apollinares.[19] During the Empire, the toga picta was

worn by magistrates giving public gladiatorial games, and by the consuls, as

well as by the Emperor on special occasions when the cloth was dyed purple.

·

Toga trabea: A

high status toga in use between the 5th century BC and the 5th

century AD. According to Servius, there

were three different kinds of toga trabea: one of purple only, for the gods;

another of purple and a little white, for kings; and a third, with scarlet

stripes and a purple hem,[20] for augurs and Salii.[21]

When worn by augurs, as a badge of

office, the toga trabea became a relatively short, rounded purple and

scarlet cloak fastened to the shoulders by broaches (fibulae). Dionysius of Halicarnassus says that those of

equestrian class wore it as well, but this is not borne out by other evidence.

·

Toga sordida: A

dark coloured plain toga worn, if they could afford the material, by the

plebeian class.

Other less well known togae include:

·

Toga exigua:

The term borrowed from Horace for a short toga worn in the 1st

century BC.

·

Toga purpurea:

The Imperial purple toga ostensibly for the use of the Imperial family. Both Emperors Caligula and Nero attempted to

control the use of purple in clothing but to little effect. The colour itself was probably not the modern

purple but more likely a dark maroon.

·

Toga rasa: A toga

with close-clipped smooth pile with some evidence suggesting it had mixed

fibres.

·

Toga contabulata: A

banded toga popular in the 2nd and 3rd centuries

AD, which may be synonymous with the toga trabea. The toga contabulata[22] may

differ in the number of colours used.

·

Laena: A

priestly toga, probably purple in colour, about twice the size of the

regular garment worn by the Flammines during sacrifices. The Laena was shaped somewhat like a toga

but worn draped over both shoulders and hung in a high curve, front and back. It was fastened at the back by a pin. By its sheer size the priest must have had an

assistant (camilla), a young boy from a respectable family, to carry the

train.

Recreating a Toga

Material Although silk, cotton, linen and mixed fibres were all known, it would appear that for the most part Romans used wool cloth to make togae. To achieve the characteristic drapery, the material used must have been pliable and not too heavy and yet, by its own weight, naturally fall into graceful folds. The textile must be soft, but with a nap that allows the folds to cling together without pinning. Modern wool cloth is often too hard and stiff to achieve the effect, and close clipped or “polished” textiles will not cling correctly and will slip from the shoulder with the slightest movement. The sourcing of a lightweight, soft and pliable flannel or similar cloth will be needed therefore to recreate a toga.

For a recreated toga, the cloth

need not be pure wool. Modern wool mixes

are an acceptable compromise to reduce costs (providing they look like what the

purport to be), but artificial fibres should be avoided. Neither does a recreated toga have to

be exclusively white, unless making a toga pura or one of its

derivatives.

It is possible that the toga was woven in one piece, compete with clavii,

on a special loom. It is certainly

possible to weave the requisite cloth on a hand loom but it will take

considerable time and the larger the toga, the more likely it will need

some shaping to drape properly. It is

therefore highly possible that togae were manufactured in two or three

separate pieces. There is also evidence

from statues that the characteristic drapery was formed by sewing in the folds,

and that piping cord was woven into the selvedge.

Colour

The Roman colour palette was much smaller than that available to modern

dyers. There was still substantial

variety, and cloth colours could be improved, altered or added to by over dyeing. The vibrant, uniform dyes

common today would not have been available in the Roman period,

however. Despite

this, archaeological evidence from wall paintings, statues, and cloth samples

suggest that some ancient colours and dyes may have been very bright when

new. The colours were not “fast” in the

modern sense, and so would eventually fade after prolonged washing or exposure

to sunlight. Nor would the dyeing

process have always create a uniform colour from piece to piece. The widespread practice of dyeing wool before

spinning, i.e. “in the fleece”, may have produced a more varied hue throughout

the resulting woven cloth. Moreover, differences

in the degree of preparation, the cleanliness of the wool fibres, the time and

care taken in the dyeing process could all impact on the final colour of the

cloth.

In

theory, unless specifically reserved or forbidden, togae could be dyed any colour.

The highly stratified Roman world would not countenance this, so colours

were reserved for use by individuals of higher social status, for particular

civic roles, or for certain responsibilities such as when in mourning. Equally, some colours may have been avoided because

they had “negative” connotations and were thus deemed socially unacceptable. Purple (“purpura”) was normally restricted

for use by the Imperial family, while white togae

were typically worn by Patricians of senatorial or equestrian rank. If they could afford one it most likely that

Plebeians might have worn lighter coloured, perhaps off-white, togae since obtaining bleached white

cloth would be too expensive for most.

Ancient

writers attest to all the colours tabulated below but only some wold be

suitable for togae:

Modern colour:

|

Roman colour:

|

Remarks:

|

A

natural reddish hued wool

|

Erythraeus |

Probably

the gingery colour seen on certain modern sheep.

|

Almond

or light tan

|

Amygdala

|

|

Amethyst

Purple

|

Amethystinus

Purpura Amethystina

|

Possibly

a reserved colour.

|

Black

or very dark Brown

|

Niger

|

Mourning

only.

|

Black

(deep)

|

Coracinus

|

Mourning

only.

|

Bright

Red

|

Russus, russeus or russatus

|

|

Brown

with a red tinge

|

Fuscus

|

Probably

the “poor man’s purple”.

|

Brownish

Yellow

|

Cerinus

|

|

Cherry

Red

|

Cerasinus

|

|

Chestnut

Brown,

|

Glandes

|

|

Dark

Blue

|

Venetus

|

|

Dark

Green

|

Paphiae myrti

|

|

Dark

Grey.

Black

or deep Brown-Black

|

Pullus

|

The

colour of mourning and self-abasement.

|

Dark

Rose Purple

|

Purpureus laconius

|

Reserved,

high status.

|

Golden

Yellow

|

Aureus

|

|

Green

|

Viridis

|

|

Green

Yellow

|

Galbinus

|

According

to Martial this was popular with the vulgar rich.

|

Grey

|

Threicia grus

Glauco

|

Mourning

only.

|

Grey,

pale or maybe pale pink

|

Albens Rosa

|

Grey

according to Ovid. The colour of

mourning and self-abasement.

|

Heliotrope

|

||

Hyacinth

|

Ferrugineus?

|

|

Indigo

blue

|

Indicum (?)

|

|

Light

Blue

|

Aer

|

|

Light

Rose Purple

|

Purpureus [dibapha] Tyrius

|

Maybe

a reserved colour.

|

Marigold

Yellow

|

Calthulus

|

|

Mauve

|

Malva

Molocinus

|

|

Pale

Lavender

|

Conchuliatus (um)

|

|

Pea

Green or

Bluish

Green

|

Prasinus

|

|

Purple

|

Purpura

|

Reserved

colour for the Imperial family. There

were four major shades: Lividus (pale);

Ruber (red); Atter

(dark) and Voilaceus (blue), although the evidence suggests that

unlike modern purple, Purpura may

have been closer to a darkish Maroon.

|

(Thalassinus)

|

||

Purplish

Red

|

Ferrugineus?

|

Wearing

this colour was possibly treasonous.

|

Red

- Blue

|

Viola Serotina

|

|

Red

or Reddish Blue

|

Heliotropium

|

|

Reddish

Orange

|

Crocotulus. Flammeus

|

|

Reddish

Purple

|

Ostrinus (Ostrum)

|

|

Reddish

Violet

|

Hyacinthinus

Ruber Tarentinus

|

|

Saffron

Yellow,

Red-orange.

Yellow

with Orange overtones

|

Croceus

|

Possibly the same colour as Crocotulus.

|

Scarlet

|

Coccinus, Coccineus, Hysginus

(um), Puniceus etc.

|

Part

of the costume of an Auger, thus it may have been a colour to avoid.

|

Sea

Blue

|

Cumatilis

|

|

Sea

Blue or

Darker

blue?

|

Undae

|

|

Sky

Blue

|

Caesicius

|

|

Turquoise

Green

|

Callainus

|

|

Violet

|

Ianthinus, Violacius, Violeus

|

|

Violet

Purple,

|

Tyrianthinus

|

|

Walnut

Brown,

Dark

Brown with Red overtones

|

Carinus

|

|

White

|

Albus

|

|

Yellow,

wax like.

Brownish

Yellow

|

Cereus

|

Possibly the same colour as Cerinus.

|

Yellow-Red

|

Luteus

|

Sizing

Determining the size of a toga is not an exact science, but from

various statues we can deduce the proportions sufficiently to recreate the

garment. The amount of cloth needed will

vary according to the size and shape of the wearer and just how full a garment

is required. The sizing tables[23]

that follow may be used, in conjunction with their associated drawings, to make

a toga adjustable to the size and shape of a particular wearer. The commonality of toga shapes means

that only a few drawings are required to represent the examples known from

different points in Roman history.

LM Wilson[23] evolved a system of individual

measurement to create a bespoke toga. “U” represents a measurement from

the base of the neck to the floor while wearing flat soled shoes or bare

foot. “G” represents a measurement of

the wearer’s girth at the waistline. So,

the equation 2.43U+G means multiply the measurement “U” by 2.43 and add the

measurement “G”.

The average person, let us say 1.74 m (5’ 10”) tall and with a waist

measurement of 92 cm (36”), will require a rectangle of cloth 5.14 m x 3.65 m

to recreate a large Imperial period toga. Modern powered looms manufacture cloth that

is about consistently 1.52 m (60”) wide, however. To approximate the correct dimensions,

therefore, will require the sewing together of two lengths of cloth to produce

a toga that, while slightly small, is still an acceptable 5 m x 3 m.

Toga

of the Arringatore (Orator) circa 3rd century BC (Figure 1):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

A to F

|

2U+G

|

||

Width at each end:

|

A to B

E to F

|

0.33U

|

||

Length of lower edge:

|

C to D

|

1U

|

||

Extreme width:

|

G to H

|

1.125U

|

||

Large Toga

of the Republican period

(Figure 2):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

A to F

|

2.29U+G

|

||

Width at each end:

|

A to B

E to F

|

0.5U

|

||

Length of lower straight edge:

|

C to D

|

1.29U

|

||

Length of upper straight edge:

|

G to H

|

1.125U

|

||

Extreme width:

|

J to K

|

1.5U

|

||

Width of lower section:

|

K to Q

|

1.36U

|

||

Ara

Pacis Augustae Toga (Figure 2):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

A to F

|

2.33U+G

|

||

Width at each end:

|

A to B

E to F

|

0.125U

|

||

Length of lower straight edge:

|

C to D

|

1.25U

|

||

Length of upper straight edge:

|

G to H

|

1.29U

|

||

Extreme width:

|

J to K

|

1.72U

|

||

Width of sinus:

|

J to Q

|

0.67U

|

||

Width of lower section:

|

K to Q

|

1.06U

|

||

Large Imperial Toga

(Figure 2):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

A to F

|

2.43U+G

|

||

Width at each end:

|

A to B

E to F

|

0.5U

|

||

Length of lower straight edge:

|

C to D

|

1.71U

|

||

Length of upper straight edge:

|

G to H

|

0.86U

|

||

Extreme width:

|

J to K

|

2.1U

|

||

Imperial Toga with

folded bands (Imperial wear only) (Figure 2):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

A to F

|

2.25U+G

|

||

Width at each end:

|

A to B

E to F

|

0.33U

|

||

Length of lower straight edge:

|

C to D

|

1.5U

|

||

Length of upper straight edge:

|

G to H

|

1.2U

|

||

Extreme width:

|

J to K

|

1.93U

|

||

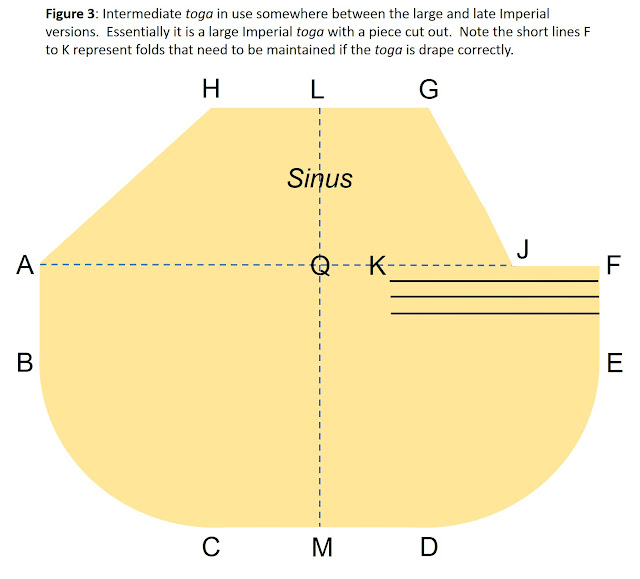

An intermediate Toga (Figure

3):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

A to F

|

2.33U+G

|

||

Width at each end:

|

A to B

E to F

|

0.33U

|

||

Length of lower straight edge:

|

C to D

|

1.5U

|

||

Length of upper straight edge:

|

G to H

|

1.2U

|

||

Extreme width:

|

L to M

|

1.93U

|

||

Width of upper section:

|

L to Q

|

0.86U

|

||

Width of lower section:

|

M to Q

|

1.07U

|

||

Cut-off:

|

A to J

|

variable ≈ 0.33A to Q

|

||

Length of folds:

|

A to K

|

indeterminate ≈ 80% A to Q

|

||

Late Imperial Toga

(Figure 4):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

A to H

G to B

|

2.36U+G

|

||

Extreme width (along line Q):

|

D to L

E to K

|

2.55U

|

||

Width of each end of the tongue:

|

H to G

A to B

|

0.32U

|

||

Length of the tongue:

|

A to N

|

1.57U

|

||

Length of upper and lower straight

edges:

|

J to H

M to N

|

0.57U

|

||

Width of sinus to cut-off points:

|

J to H

M to N

|

0.75U

|

||

Width of lower edge to cut-off points:

|

G to F

|

0.375U

|

||

Width of sinus:

|

Q to line KL

|

1.18U

|

||

Late (Eastern) Empire Toga

(Figure 5):

|

||||

Extreme Length:

|

B to F

|

2.125U+G

|

||

Width of end:

|

A to B

|

150 mm

|

||

Width of end and intermediate:

|

G to F

K to D

|

250 mm

|

||

Length of upper straight edges:

|

H to J

|

0.5U

|

||

Extreme width:

|

E to L

|

0.75U

|

||

Length to point of widening:

|

B to C

|

1.07U

|

||

Length to end of widening:

|

B to D

|

1.43U

|

||

Outline Drawings of Togae

The

drawings included here are simplified versions of those in Wilson (1924). The dates quoted in the descriptions are

approximate. There is evidence that

styles were worn for centuries after they were first popular. Reliefs on the Ara Pacis, for example,

suggest that different wearing styles coincided even if, at the time, some may

have been deemed “old fashioned”.

To clarify the terms

used, the sinus is that part of the toga that is folded back to obtain the

characteristic draping. The folds may

have been sewn or pinned in place. The clavus, on the other hand, is the

coloured (purple) edging. There is

evidence that the edging may have been sewn on after the toga had been trimmed to size for the wearer.

Donning a Toga

Most Romans did not like wearing the toga as it was hot, heavy and

uncomfortable. To wear one took a deal

of preparation and at least one other person to help the wearer put it on. The toga

was impractical day wear needing constant adjustment to preserve the correct

draped form, and to stop it simply falling off.

Wearing a toga will be quite possibly a very alien concept for

people used to modern tailored clothing.

Swathed in metres of material that must be precisely draped to be worn

properly, the left arm and, occasionally, hand dedicated to supporting the

voluminous garment and restricted to walking in short, measured steps can be an

art that requires practice.

A full toga cannot be simply “slipped” on but takes the assistance

of two or three people. Yet, evidence on

how put on a toga does not survive and modern wearers may have to

experiment with the most effective way of doing so. The following guidance is offered to those

assistants charged with dressing the toga wearer:

1. The wearer stands erect with their arms

extended laterally at shoulder height, i.e. in a cruciform stance. Other than holding a fold or slowly rotating

when instructed, there is little for the wearer to do.

2. The toga is prepared for donning

by gathering the folds, which are then placed, from behind the wearer, over

their left shoulder. The folds should be

uppermost and hang down wearer’s front, with the bottom edge reaching to the

level of the knee or mid-calf. The folds

should be adjusted as required to drape properly. The wearer can assist by bending his left arm

at the elbow and gripping the material in place.

3. Keeping the folds together, drape the

material down the wearer’s back, looping up under their right arm, across the

chest (the wearer’s left hand must be out of the way) and once again over the

left shoulder. The depth of the swag

will depend on how long and full the toga has been made. Tucking the material into a belt may help the

draping on the wearer’s right side.

Depending on the available space it may be advantageous to get the

wearer to perform a slow quarter or half turn to the right.

4. If the toga is particularly long,

the remaining material should be passed over the right shoulder (from back to

front) and under the right forearm to cradle the arm in a sling before again

passing over the left arm or shoulder.

Alternatively, excess material may be tucked beneath and into the folds

created by the first pass across the body.

Endnotes:

1. William Smith, LLD; William Wayte; G. E. Marindin, ed

(1890). "Toga". A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, London:

John Murray.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0063&query=head%3D%.

2. Livius, Titus (ca. 1st century BC). "Book

III: The Decemvirate", chapter 26, Ab Urbe Condita.

3. Spart. Sever. 1, 7. As cited by The Dictionary of

Greek and Roman Antiquities.

4. Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius (121 CE). 15.2, The Life of

Claudius. "In a case involving citizenship a fruitless dispute arose

among the advocates as to whether the defendant ought to make his appearance in

the toga or in a Greek mantle..."

5. Plinius Caecilius Secundus, Gaius (ca. 105 CE). Line 3,

epistle 11, book 4, Epistulae. "Idem cum Graeco pallio amictus

intrasset - carent enim togae iure, quibus aqua et igni interdictum est..."

("Likewise he would have gone clothed with the Greek garb - for those who

have been barred from fire and water are without the right of a toga...")

6.

Tullius Cicero, Marcus (63 BC). Pro Rabirio

Perduellionis Reo ("For Rabirius on a Charge of Treason").

"Rabirius... was now accused of... wearing the dress of an Egyptian."

7.

Suetonius

Aug. 40.5

8. Bunsen, M. Encyclopaedia of the Roman Empire, New York

(ISBN 0-8160-2135-X)

9. cf. Mart. viii. 28, 11. As cited by The Dictionary of

Greek and Roman Antiquities.

10.

cf.

Polybius, x. 4, 8. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

11. Liv. iv. 25, 13. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and

Roman Antiquities.

12. Liv. xxiv. 7, 2. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and

Roman Antiquities.

13. cf. Cic. post red. in Sen. 5, 12. As cited by The

Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

14. Zonar. vii. 19. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and

Roman Antiquities.

15. Liv. xxxiv. 7, 2. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek

and Roman Antiquities.

16. cf. Cic. Phil. ii. 4. 3, 110. As cited by The

Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

17. Liv. xxvii. 8, 8; xxxiii. 42. As cited by The Dictionary

of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

18. post red. in Sen. 5, 12. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek and Roman

Antiquities.

19. cf. Liv. v. 41, 2. As cited by The Dictionary of Greek

and Roman Antiquities.

20. cf. Isid. Orig. xix. 24, 8. As cited by The

Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

21. ad Aen. vii. 612; cf. ad vii. 188. As cited by The Dictionary

of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

22. Apuleius, Metamorphoses, 11.3. “Toga contabulata”

appears to be a relatively modern, albeit useful, term.

23. Wilson, L.M., (1924), The Roman Toga, The John

Hopkins Press, Baltimore [Amended].

24. Olson, K, (2002), Fashion Theory: The Journal

of Dress, Body & Culture, Volume 6, Number 4, pp. 387-420(34), Berg

Publisher.